Thirty years ago today, I was asleep in my university bedroom when I was woken by a hammering at the door. It was likely around 8.30, 9 o’clock, in the days when I could sleep late, and I opened the door to find a note.

Phone home.

This was not some ET tribute. My dad had died.

I knew immediately that this was why I needed to call, it was expected news. Students didn’t have mobiles back then and I’d only been at uni a week so my housemates hadn’t yet agreed a house landline. The porter had taken a message from my mum and I needed to call her from the payphone in the lodge.

I’d been planning to write something to mark the occasion but I hadn’t made up my mind what that was going to be until I went back to Mum’s this past weekend. While I was there, it occurred to me that – massive revelation incoming, wait for it – we’ve all altered with age, me, my mum, my sister. Only my dad hasn’t.

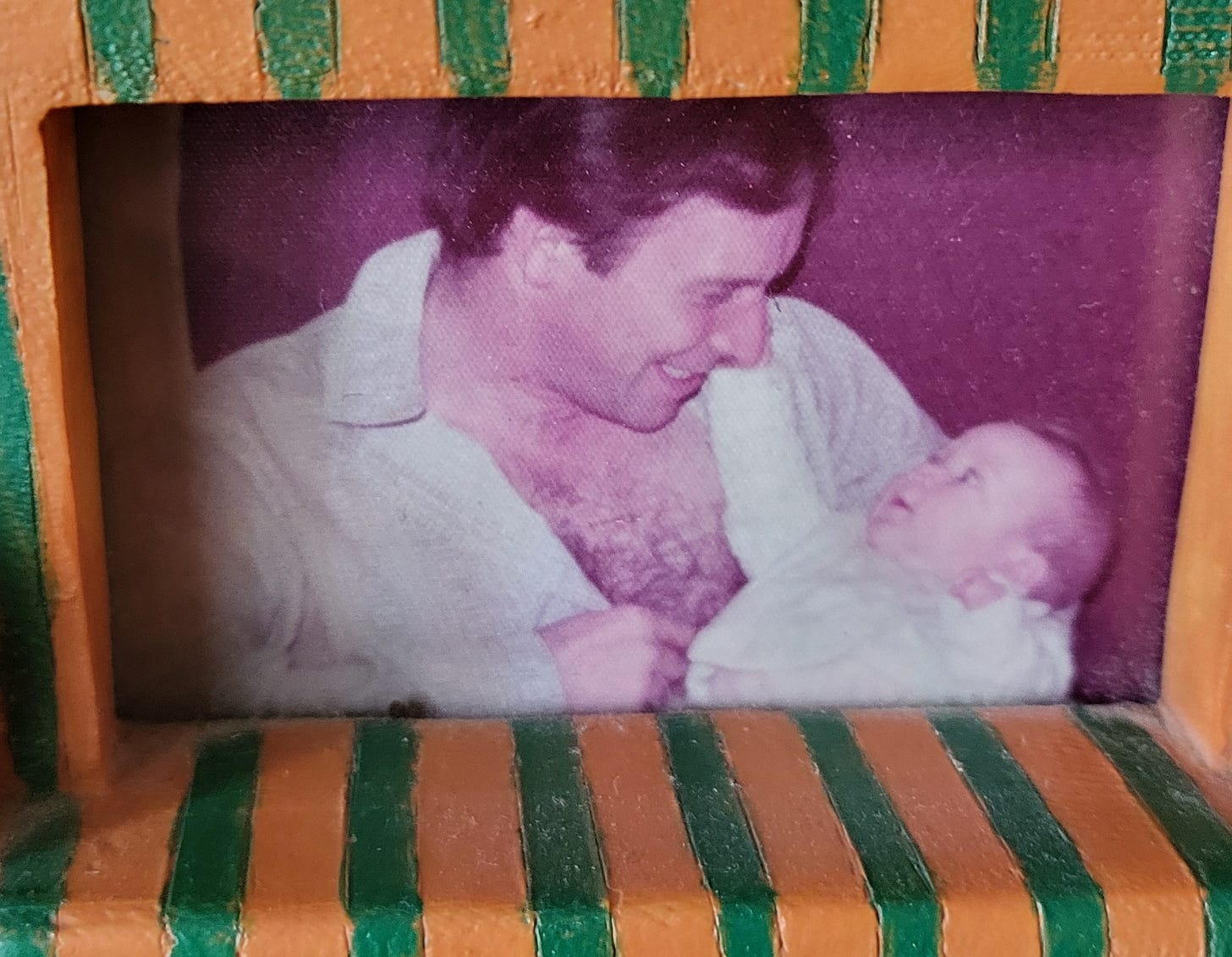

Dad was born in 1939 and I have no photographs of him as a child or a young man. In this day and age, the idea of not documenting your children is so strange and yet it’s a modern phenomenon. Of course there aren’t any pics from that time. Somewhere at Mum’s house is a picture of their wedding day, and also a picture of them on a narrow boat holiday, so from the early-mid 1970s, but the earliest picture I have of him is one of him holding me as a baby. In it he must have been 36 years old. My memories of him are mostly of a man in his forties. He was 55 when he died.

He always did seem of a different generation. I don’t mean in the way your parents will always be slightly different to you, with older cultural touchstones, I mean that his ideas of family life and roles within the family were very old fashioned. He was the breadwinner, the one we were all supposed to rely on, he made decisions, he would be the arbiter of which boots he would consent to buy you or what we would watch on TV. He was the Man of the House.

Last weekend the three of us spent some time giggling together, in that way that you do with people you’ve known very well for years, the old jokes and tongue in cheek ways of referring to each other resurfacing. We always did better when he’d gone out, it was more relaxing that way and Mum wasn’t old fashioned and was happy to watch Top of the Pops.

I find it hard to write about him now, simply because I don’t remember a lot of details. So here are the things I do remember:

· He gave up smoking when I was ten years old but I associate the smell of his ratty red towelling dressing gown with the tin of tobacco that he kept in the pocket.

· He was really interested in me applying to university and studied all the prospectuses when they arrived to let me know the ones he liked. He drove me to look around a couple of them and we got lost in Sussex Uni’s library and laughed at the filthy looks we got from studious types.

· He used to bang time to music he played in the car with his cygnet ring, which he bashed between the steering wheel and the window.

· Mozart’s Horn Concerto. Kenny Rogers. Blanket on the Ground by Billie Joe Spears. Solitaire sung by Neil Sedaka. King of the Road. The William Tell Overture. Crystal Gayle.

· He used to come in from work and catch the headlines on the six o’clock news before turning over to watch the western that was screened on BBC2.

· He voted Tory at every election. I am unsure what he would have made of Brexit or the NF-lite policies of the current Tory party.

· He loved to eat smoked kippers and grilling them would stink the house out.

· He would yell at motorists who didn’t know the width of their vehicles ‘you could get a bleedin’ Sherman tank through there!’ or if they were hesitant in pulling away: ‘are you waiting for a bleedin’ gold plated invitation?’ (no one says bleedin’ as a swear these days do they?)

· Tottenham Hotspur FC. One of the only times I saw him cry was a furtive tear at their 1991 FA Cup victory.

He also liked travel, big West End shows and going to Northumberland, especially Alnwick. These were not activities he did with his family. I wanted to say that he was often quite serious but that isn’t strictly true, as he did have a good sense of humour, one that in many ways I share. But he lived mainly to work and did a serious job at Kent Fire Brigade, supervising calls and support, and offering extra service when needed for things like the Deal Barracks bombing, the Zeebrugge ferry disaster, and sending a team to the Armenian earthquake. If he was on call, he would rush off with his blue light flashing, and so it felt very much like he was important and serious and the rest of us were less so.

No examination of his death is wholly complete without mentioning that this was the time when we discovered the extent of his infidelity, and the years-long relationship he had with another woman, and also that he left us to go and be cared for by her at the end of his life. This detail has essentially hung over much of my thoughts about him for many years and has always prevented me from fully mourning his death. He died too young but if I’m honest, life was a lot easier once he wasn’t around. And if that sounds harsh, then I won’t be apologising for it. When someone dies, I think we often remain the age we were when we knew them and I know very well that my 19-year old self dominated my thinking about him for a long time.

These days I consider that, perhaps it would have been better if he’d been more honest about what he wanted from family life, not with us, but with himself. He wanted someone pliant, submissive and soft. When we visited, my mum and I, when we visited his girlfriend's house after his death to return some gifts and photos she’d asked for, her house was so hushed, with deep pile carpets, comfy sofas and huge swags of curtains. It felt insulated and soft and terribly middle class and it occurred to me how different it was to our house, with hard floors, dog hair clumps and Radio 1 as constant background, how messy and bolshy we all were. In some ways, it’s no wonder he preferred it there; in others, I think ‘well you knew what you signed up for and you couldn’t stick it.’ None of us are likely to be pliant and submissive, back then or now as we get the chance to age in the way that he did not.

Thinking of him now, I do wonder at this idea about life choices and redemption and second chances. And having been back to Mum’s house last week, I also think about how to grow old in the way you want. These things were denied to Dad because of cancer. I think it likely at some point once me and my sister had left home, he would have left too and tried to pursue a life with the pliant girlfriend, possibly retirement in Northumberland. I also think that it would have been easier to have a relationship with him as an adult. He was never a natural father or generally good with children – he didn’t do kickabouts in the garden and never sat through school plays or presentations without making excuses about leaving for work. (He would arrange with them to page him so he didn’t lose face with other parents. I once told a friend this, because his behaviour was totally normal for me growing up, and she stopped in the street in surprise and shock.)

Here's what I’ve learned, from having him as a father, having spent my adult life trying not to be like him, to instead be open to inclusion and tolerance and support, to never vote Tory, to be a union rep at one point (pretty certain he turned in his grave that day), having found a life partner who is generous and supportive and involved in family life, to listen to my daughter’s music choices and not mock and make her feel bad about them, having decided to be as fully present with our life together as I can, having vowed not to be submissive and pliant, all this – and there is still once in a while a pang to hope that he would have been proud of me.

Rest in peace you old bastard.

Jack of All Trades is a free newsletter, mainly due to me worrying that no one in their right mind would pay for my ramblings. But I’d love it if you do fancy subscribing - click the button below!